Clunkers & Creampuffs

Chapter 17: Wheels for the Fifties Workingman

Car-buying wage-earners share in postwar prosperity as

looser credit helps families reach the "American Dream"

by James M. Flammang

Upward mobility in age of postwar prosperity

demanded a bigger, better car, like this 1957 Dodge.

Full employment and rising wages made it possible

for workers to drive home late-model, or even

brand-new, automobiles.

As the expanding suburbia steadily transformed the American way of life, middle-class families weren't the only ones to covet – and acquire – one of the enticing new automobiles of the late 1950s. Working-class folks also were ready to move higher on the family-car spectrum. Why put up with that wheezing 1939 Dodge or 1949 Pontiac when a colorful, increasingly powerful machine might be obtained by simply signing on the dotted line of a dealer's sales contract.

Unemployment was low, after all. Jobs were plentiful and wages were rising. Whether they toiled at a desk or a machine, in an office complex or a traditional factory, breadwinners craved some fresh, modern rewards for their labors. Already in 1956, 85 percent of workers owned a car and drove 10 or more miles to work.

For plenty of wage-earners, upward mobility (literally) could mean moving up from the clunker you've kept running for years to a more dependable, not to mention attractive, contemporary model. Rather than a current version of that six-year-old "plain Jane" family sedan that's been acting up a bit, maybe a late-model is finally in the cards for your family. Or, who knows, maybe even a brand-new hardtop is possible. All you need is the down payment, and you can drive home in style.

Moving upward could mean going from a Ford or Chevrolet to a Mercury or Buick, for those who preferred to stay within the same car make. For those who craved a bit of variety, how about trading in your Plymouth for an Oldsmobile; or switching from Pontiac to Studebaker.

If you're not yet ready to take the full plunge into a brand-new automobile, buying a higher-level used car could provide transportation that's similarly respected, and even envied. All the more so, if it's loaded with gadgets and accessories, taking advantage of the new, imaginative options that keep coming from the automakers. As cars grew bigger in the late Fifties and into the Sixties, their value in terms of conspicuous consumption – favorable, compared to your neighbors' – would be even more evident.

A few fortunate families could make their version of that American Dream even more fantastic. How about a Cadillac? Or a fully-loaded convertible? A new one might still be beyond reach, but the basic economic concept of depreciation just might make it feasible to drive home one that's pre-owned (a term that wasn't quite in the American lexicon as yet).

Whether new or secondhand, a car beyond the middle ground could really give a fellow something to "work for" – a reason to endure a tiresome job. Younger folks, in particular, were especially drawn to that benefit of modern-day motoring, as observed in the next chapter.

Time Payments make it happen

Even as installment payments became more available, many older people who retained the "Depression mentality" had difficulty adjusting to the new prosperity. For the young? No such worries.

By 1955, finance companies were offering credit with terms as long as 42 months. Used cars could be purchased for as little as 12 or 15 percent down, with up to five years to pay the balance. That was quite a long time, for a car that had at least one prior owner; but most credit-worthy shoppers seemed to be largely unfazed by economic facts. Besides, the Great Depression was far in the past. Contemporary Americans believed that prosperity would last forever this time, with regular wage increases anticipated, even if the average wage in 1955 was only $76 a week.

Not everyone was able to obtain credit, of course, for a better car or for anything else, including basic necessities. Applicants living in poor neighborhoods (in certain areas of a city), or in a hotel or rooming house, could expect to be turned down. So could those who lacked suitable references (including divorced women), farm workers and other transient laborers, and those employed in what might be considered unstable occupations (cab drivers, longshoremen, waitresses, actors, entertainers, low-grade military personnel, or transient construction workers). In addition, of course, to those with no occupation at all at the present time.

Persons of color in the Fifties couldn't expect to be welcomed at the finance person's desk or office, regardless of their employment status or other decisive factors. Neither could many immigrants. For those in any of these categories, their only choice for private transportation, as in the past, was sitting on the lot of a lower-level used-car merchant.

According to a 1952 survey, 40 percent of families making less than $2,000 per year owned a car, versus 60 percent of those earning $2,000 to $3,000. A 1959 study found that 30 percent of used-car buyers earned less than $5,000 annually, and 70 percent of them would rather have a new car. At that time, more than 60 percent of motorists had never bought a new automobile. Used cars still ruled.

The impoverished might have to pay cash for a potentially troubled vehicle and do without insurance, but at least cheap (if unreliable) private transport did exist. If credit was available, it came with the least appealing financing terms. Many well-off Americans were not known for kindly attitudes toward the poor, especially if they spotted someone they perceived as a low-income person behind the wheel of a Cadillac. Interest in and ownership of fancy cars among people on the bottom of the income scale was hardly unknown. Plenty of those prestige automobiles were doubtless rough rather than pristine, and greatly outnumbered by ordinary models.

According to one analysis in 1954, an average worker had to put in 30 weeks of work to buy a new automobile (average retail price: $2,168). Back in 1925, such a purchase demanded 37 weeks of work ($910 retail). In 1980, about 27 weeks would be needed ($7,823 retail).

New-car prices rose 27 percent between 1946 and 1955, but manufacturing earnings rose faster. A factory worker had to toil almost 33 weeks to pay for a new 1949 model; but only 27.5 weeks for a '57.

From the dealer's perspective, if not the customer's, better used cars split into three categories:

• Low priced (promising utility but little glamour)

• Popular priced (1 to 3 years old; was low-priced when new)

• Quality (also 1 to 3 years old, worth about as much as a new low-to-medium priced car)

For the most part, working people still envisioned new cars as a dream on the showroom floor, not an occupant of one's own driveway. Or perhaps more accurately, parked along the curb in front of their apartment. Owning one would be nice, but wiser to accept what you can afford.

Workers had more money than before, steadier jobs, and a presumption of a secure future. Mid-1950s workers expected steady wage increases and minimal risk of unemployment. Wartime shortages now seemed to be forgotten totally. "Buy Now - Pay Later" increasingly seemed like a reasonable lifestyle for most Americans, replacing the notion of "delayed gratification." Hardly anyone anticipated the upcoming 1957-58 recession.

In 1953, an estimated 60.6 percent of urban families were considered "wage earner" rather than white collar. For the nation overall, 52.3 percent were wage workers. Wages had been rising faster than car prices, and faster than the Consumer Price Index (CPI) since World War II. In terms of discretionary income as a percentage of total family income, wage-earners were actually faring better than other employees. Even a number of older workers were losing their "Depression mentality," though some continued to fear debt. Especially long-term (or lifetime) debt.

New ways of purchasing cars, incidentally, coincided with changing buying patterns for many goods for the home, including radio and TV sets, washing machines, and kitchen appliances.

Early Depreciation could help cash-challenged customers turn to late-models

According to one study, the relative price structure of used cars (in terms of depreciation) changed little from 1921 to 1957.

Every car on the road is "used," people were reminded, so why pay that hefty amount for early depreciation? One source calculated that in the Fifties, 38 percent of a typical car's initial value was gone after its first year in operation. Half was gone after the second year, and two-thirds after four years. After five years, only 18 percent of the vehicle's original value remained.

Cars from independent manufacturers, dubbed "orphans" (those produced by automakers that no longer existed), and "off-breeds" generally suffered from higher first-year depreciation. For that reason, they could be better values for the customer in the used-car market.

How much of family income were early postwar motorists spending on their cars? Quite a bit. Operating costs of a new car in 1948, according to one source, averaged 8.5 cents per mile, or $851 per year (assuming the car cost $2,000 when new). In comparison, during the first decade of the 20th century, a typical motorcar owner was paying 10 to 18 cents per mile to keep it operating.

So, had the promise of "a car for everyone" finally come true? Yes, for nearly everyone with a steady job and a lack of demerits in their personal financial record. Only a relative handful of Fifties workers who still lacked a regular paycheck rolling in needed to be denied that Number One "American Dream: goal: a private car. But they'd have to be judged creditworthy, and ready to sign up for many months of seemingly-ceaseless payments.

The Coming Compacts ... imports, too

Impact of compact American cars (and imports) on used car market

Depending on where you lived, small cars – primarily foreign makes – might be rare or reasonably common. In big cities and on college campuses, economical import models captured quite a number of stalwart, knowledgeable fans. A visiting parent might see a Hillman Minx or Morris Minor (British), Renault 4CV or Dauphine (French), DKW or Borgward (German), or sprightly Italian Fiat 500. Students or professors at some campuses might even be piloting a micro-size BMW-built Isetta or motorcycle-like Messerschmitt. Far more likely to be seen on the street were the first of the Volkswagen Beetles with their distinctive profile, oval back window (until 1958), and tiny rear-mounted, air-cooled engine.

Elsewhere, in some of the more rural regions of the country, drivers of imported cars were more likely to be viewed as eccentric and, like their cars, vaguely foreign – worthy of suspicion, if not scorn. "Buy American" was not yet a common slogan among marketers, but plenty of drivers of strictly American makes already endorsed that theme. Practical-minded motorists were increasingly drawn to imports, applauding their sensible, economical merits, but they were grossly outnumbered by the big-car crowd.

Imported cars took a while to draw much attention at dealerships or among potential customers, partly because of their skimpy numbers on the road. The general public felt (not without cause) that they were more difficult and costly to repair. Simply purchasing a replacement part from the 1950s through the 1970s could be a tedious and expensive ordeal.

Familiar brands, led by Volkswagen and several of the British makes (Austin, Ford Anglia), were generally acceptable to a larger audience, once their presence on the nation's highways became numerous and familiar. So were the two-passenger sports cars from Britain: MG, Austin-Healey, Jaguar, Sunbeam, and so forth. Not to mention Germany's Porsche and Italy's Alfa Romeo.

With the exception of Volkswagen, though, none of the 1940s/50s small cars made a large dent in either the new- or used-car market. On the other hand, public interest may have been tweaked a bit when the recession of 1957-58 demonstrated that Fifties prosperity wasn't a perpetual certainty.

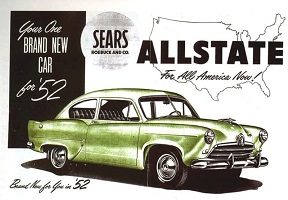

As for the American automakers, compact cars had been tried before, even before World War II. Several emerged in the early Fifties, including the Hudson Jet and Kaiser's Henry J (also sold under Sears Roebuck's Allstate brand, pictured at right). An enthusiastic group even coveted the subcompact, down-to-basics Crosley, as well as a handful of short-lived microcars that emerged now and then. Most successful (and conventional) was the Nash Rambler, introduced in 1950, which remained available and reasonably popular long after the Nash brand name disappeared in 1954, finally expiring in 1969.

As mentioned previously, the motivation studies in the 1950s suggested a small market for small cars, partly because some observers insisted they were unsafe. Psychologists also wondered if potential owners in suburban America really didn't want to seem small themselves, in an era when autos would be growing substantially in size. Already, bigger meant better to many eyes.

The automotive market changed sharply in 1959-60, when nearly all of America's automakers brought out new smaller (and cheaper) cars. Bracketed between two recessions (1957-58 and 1960-61), the new American compacts gave buyers of standard domestic makes a welcome alternative. Not only were they manageable in size and less costly than their bigger counterparts, but they promised significantly better fuel economy. Gas mileage wasn't nearly as big an issue at that point as it would become a decade or two later, but a healthy dose of frugality could be quite appealing to hard-working families.

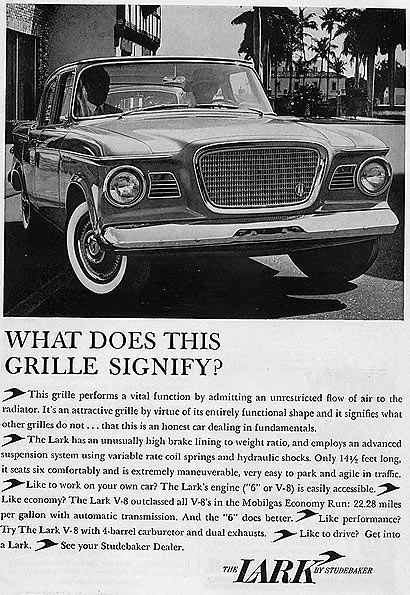

Studebaker was among the first, introducing its compact Lark (left) in 1959. Not only was an ordinary four-door sedan available, but Studebaker built the Lark in hardtop and convertible form, along with a station wagon. Ford launched the Falcon sedan and wagon as a 1960 model, along with its Mercury Comet counterpart. Plymouth and Dodge debuted the Valiant and Lancer, respectively, for the 1960 model year. All five had conventional front-engine/rear-drive powertrains.

Studebaker was among the first, introducing its compact Lark (left) in 1959. Not only was an ordinary four-door sedan available, but Studebaker built the Lark in hardtop and convertible form, along with a station wagon. Ford launched the Falcon sedan and wagon as a 1960 model, along with its Mercury Comet counterpart. Plymouth and Dodge debuted the Valiant and Lancer, respectively, for the 1960 model year. All five had conventional front-engine/rear-drive powertrains.

Chevrolet took a completely different tack, developing the rear-engine Corvair. Produced as a coupe and sedan, and later a convertible, the Corvair ran into trouble from Ralph Nader's critique of the auto industry, Unsafe at Any Speed, which questioned the safety of the car's rear-engine chassis.

Additional compacts followed in 1961, with three from General Motors: Buick Special, Oldsmobile F-85, and Pontiac Tempest.

Though cheaper than full-size cars at first, second-generation compacts could have more powerful engines, and buyers might choose from longer option lists. Sporty versions joined the lineups, giving shoppers choices beyond a basic four-door sedan.

Studebaker's compact Lark failed to keep the company afloat. Production moved to Canada for its final two years (1965-66), turning out a version of the Lark but abandoning that model name. (Meanwhile, Studebaker's lusciously-shaped Hawk hardtop coupes faded away.)

Impact of compact cars and imports on the used-car market

Neither dealers nor industry experts initially felt threatened by the trickle of smaller cars that hit the market through the Fifties, starting with the Volkswagen Beetle that first reached the U.S. in 1949. Industry leaders largely dismissed the burgeoning success of both foreign cars and Nash Ramblers as "a revolt of the intellectuals," according to Business Week. Despite that scorn, both imported and domestic compact and mini-sized models would have a powerful impact on new- and used-car sales at decade's end and far beyond.

When the American compacts arrived at dealerships, many in the industry feared they would upset the used-car market. Prices had been high for both new and used cars before the first (1959-60) compacts arrived. Demand had been strong for costly (say, $2,000) used cars, but those new compacts might be even more tempting.

Used cars met the new challenges. Their average prices dropped by about 15 percent between late 1959 and early 1961, but rebounded fairly quickly, first meeting the challenge of the domestic compacts, then the even greater obstacle of the imports.

As for those imports, with the exception of Volkswagen's Beetle, which benefitted from some of the most effective advertising ever created, not many foreign makes gained wide popularity as used cars in the 1950s or '60s. Mini-sized Morris Minors, Dauphines, and dozens more passed largely unnoticed through the secondhand marketplace.

Click here for Overview: Casual History of the Used Car

Click here for Chapter 1: Early Days - Rich Men's Playthings, Poor Men's Dreams

Click here for Chapter 2: Ford's Model T and the Masses

Click here for Chapter 3: Production and Prosperity

Click here for Chapter 4: "Easy" Payments

Click here for Chapter 5: Family Cars and Family Life

Click here for Chapter 6: Five-Dollar Flivvers

Click here for Chapter 7: Rise and Fall of the Used Car

Click here for Chapter 8: Saturation and Salesmanship

Click here for Chapter 9: A Global Blowout

Click here for Chapter 10: Selling in Hard Times

Click here for Chapter 11: Wheels for the Workingman

Click here for Chapter 11: Okies, Nomads, and Jalopies

Click here for Chapter 13: Motoring in Wartime

Click here for Chapter 14: The Postwar Boom

Click here for Chapter 15: Chromium Fantasies

Click here for Chapter 16: Dealers Face Image Problem

Click here for Chapter 18: Teens, Rods, and Clunkers

Click here for Chapter 19: Everybody Drives

Click here for Chapter 20: Personal History of Clunker Ownership

© All contents copyright 2022 by Tirekicking Today